Buddhist cosmology is one of the least explored and most fascinating aspects of this ancient tradition. Although today interest in Buddhism tends to focus on topics such as meditation, ethics or philosophy, the vision of the universe presented by Buddhist texts offers a rich narrative that connects the spiritual, the moral and the cosmic. In this interview, we talk to Óscar Carrera about his new book The Buddhist Universe: According to Early Sources, published by Editorial Kairós in 2024. Carrera shares his reflections on Buddhist cosmology, addressing the challenges of reconstructing such a complex vision from scattered sources. In addition, it analyzes the modern interpretations that tend to psychologize these ideas and reflects on the dialogue, or its absence, between Buddhist cosmology and contemporary science. Through his answers, the author invites us to look beyond modern simplifications to explore a universe that, although distant in time and culture, continues to offer profound lessons about the mind, morality and our relationship with the cosmos.

Óscar Carrera has a degree in Philosophy from the University of Seville and specializes in South Asian Studies from the University of Leiden. In her master's thesis, she delved into the study of music and dance as reflected in literature written in the Pali language. Throughout his career, he has published multiple articles in journals specializing in Buddhism and is the author of several works, both fiction and essay, including The nameless god and Human mythology, which reflect their ability to combine intellectual rigor with narrative creativity. Committed to cultural outreach, he regularly collaborates with Buddhistdoor in Spanish, where he writes articles and provides analyses on various aspects of Buddhism.

BUDDHISTDOOR IN SPANISH: In your book, you research and delve into Buddhist cosmology based on Pali sources. What motivated you to explore this aspect of tradition instead of other more common topics, such as meditation or ethics?

One way to respond is that, from a historical perspective, those other issues don't seem to be as common. It has long been debated whether there is an ethic in pre-modern Buddhism, that is, a systematic moral reflection as opposed to simple morality, to recommendations and precepts that evade philosophical research because they come from an enlightened authority. According to ethicist Damien Keown, we barely find ethical treatises in classical Buddhism. If this is true, “ethics” in Buddhism is largely a modern cutoff: its moral rules in “our” field of moral reflection. What can I say about meditation, an initiatory activity today promoted to a mass audience through Apps! Often another de-ritualized hybrid, conceptually secularized and psychologized as much as possible. I will add that in the Pali tradition, meditation manuals in the strict sense are not abundant either. These and other cases indicate that part of what we call Buddhism today is a transplant of practices or concepts into the familiar terrain of modern worldviews, but I already know those and they are not the result of more than two millennia of Buddhism.

BDE: The cosmology you describe was systematized in a late period, although it is based on discourses in Pali. What challenges did you encounter in reconstructing this view of the cosmos from scattered sources?

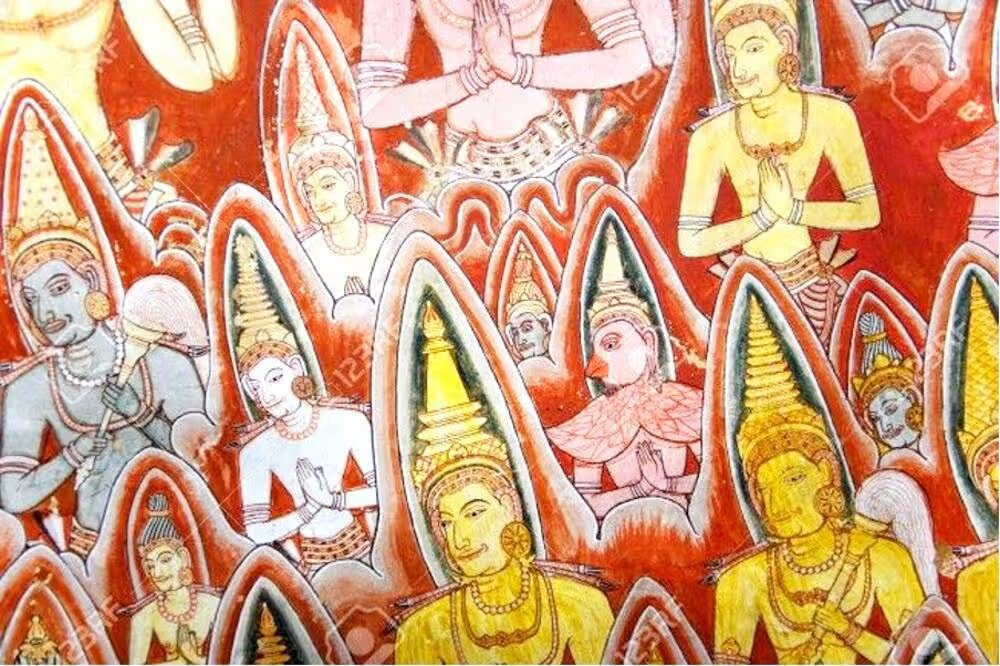

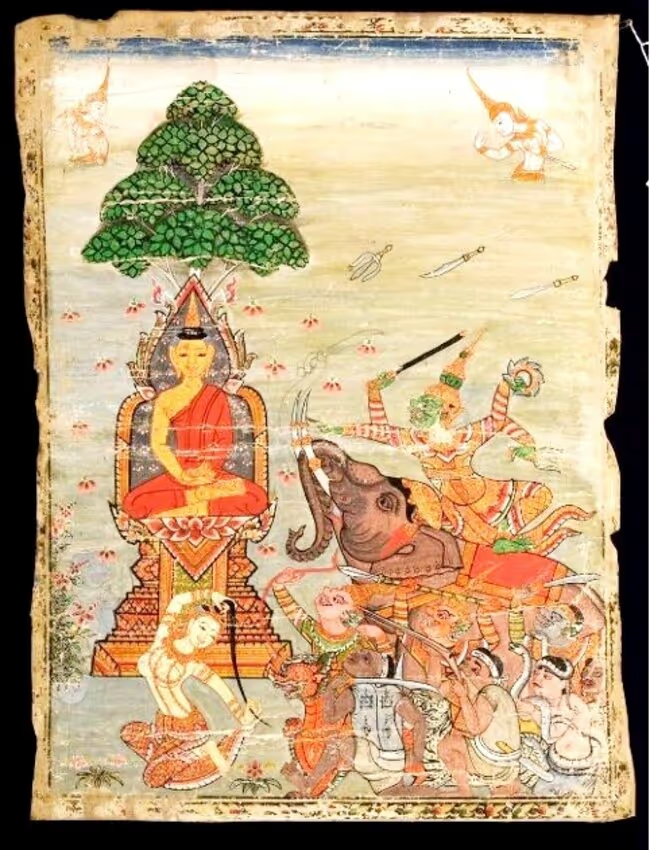

The texts used, both canonical and commentary, are catastrophically plural, a chorus of dissonant voices; in this field of cosmology more than in others. The book attempts to contain tensions and present a polished surface, but this is only a pedagogical strategy. For example, in the most common characterization Erāvaṇa is a polycephalic elephant that serves as a ceremonial saddle for Indra (Inda, Sakka): every good Indian deity has a saddle and we can imagine Indra on his elephant, like the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, perhaps going to battle against the Titans (Asura) in its formidable frame. But in the comments, Erāvaṇa is described as a kaleidoscopic being, within the limits of imagination: he has thirty-three heads with seven fangs on each head, seven lakes in each tusk, seven plants in each lake, seven lotus flowers on each plant, seven petals on each flower, seven goddesses dancing on each petal... The gods are usually kilometers tall; other times they are human tall and sometimes dozens can congregate at the tip of a needle. Our criteria of reality and representation dissolve into thin air when we approach the inhabitants of other realms of rebirth, and we find passages that are very aware of this, while others are of a flatter realism.

BDE: We observed an interesting phenomenon in the contemporary spread of Buddhism: while canonical texts present a rich cosmology with diverse planes of existence and supernatural elements that swarm the Buddhist universe, such as the asuras, the figure of Māra and the nagas, modern interpretation, especially in the West, focuses almost exclusively on its philosophical and meditative aspects. Do you consider that this transformation responds to a necessary adaptation to the contemporary world or does it represent a simplification that compromises the comprehensive understanding of this tradition?

It is what it is: the creation of a new form of Buddhism that did not exist before and that would not have emerged from any other context of cultural exchange. A new hybrid and mixed-race Buddhism, as are all regional and historical Buddhists, although this one has to build longer bridges (since it enters into dialogue with currents such as scientific materialism or empiricist skepticism, antipodal to any previous Buddhist culture). In that labyrinth of mirrors we wander, sometimes very lost in our rhetoric, delighted by the sound of our own voice. Although my book is also guilty of cultural adaptations, which are intended to be conscious (for example, I highlight elements of “magical realism” because I think they will arouse interest in the reader), I understand that the most rational movement of someone who finds himself locked in a labyrinth is to try to get out. At the very least, to take the first step, which is to shut up for a few moments: to try to silence the inherited worldview for a few moments.

BDE: The Buddhist texts of the Theravāda tradition describe a correspondence between meditative states (including jhānas) and cosmological planes. How does this correspondence between inner experience and the structure of the universe illuminate Buddhist understanding of consciousness and guide your meditative practice?

The correspondence provides a vast backdrop to the meditative experience, which reveals a crossroads between worlds: some meditative states are not experienced only in the human world, in that privacy or interiority with which we moderns endow the mind, but they are a bridge to other worlds. By meditating, we get used to the “frequencies” of other planes of rebirth and this will influence destiny after death, as the mind will jump to what is of a similar nature. In any case, I understand that mental states are transverse to the planes of rebirth: it's just a certain absorption (Jhāna) of a human meditator is only the mental reflection of certain heavens. Absorption is a fundamental reality accessible to various planes, but only in those heavens is it the default mental state; on the planes that are “below” them, such as ours, it is difficult to obtain, and for those who are above in the heavenly meditative progression it is a trinket. I confess that it is difficult to pronounce itself in this area because Buddhism, like other Indian schools, assumes this mind-cosmos correspondence and rarely exposes it explicitly; its contours and implications remain fuzzy.

BDE: The Buddhist texts of the Theravāda tradition describe a correspondence between meditative states (including jhānas) and cosmological planes. How does this correspondence between inner experience and the structure of the universe illuminate Buddhist understanding of consciousness and guide your meditative practice?

The correspondence provides a vast backdrop to the meditative experience, which reveals a crossroads between worlds: some meditative states are not experienced only in the human world, in that privacy or interiority with which we moderns endow the mind, but they are a bridge to other worlds. By meditating, we get used to the “frequencies” of other planes of rebirth and this will influence destiny after death, as the mind will jump to what is of a similar nature. In any case, I understand that mental states are transverse to the planes of rebirth: it's just a certain absorption (Jhāna) of a human meditator is only the mental reflection of certain heavens. Absorption is a fundamental reality accessible to various planes, but only in those heavens is it the default mental state; on the planes that are “below” them, such as ours, it is difficult to obtain, and for those who are above in the heavenly meditative progression it is a trinket. I confess that it is difficult to pronounce itself in this area because Buddhism, like other Indian schools, assumes this mind-cosmos correspondence and rarely exposes it explicitly; its contours and implications remain fuzzy.

BDE: In your book you describe a Buddhist universe that is inherently moral, where the actions of beings determine their place in the structure of the cosmos. How does this vision of an ethically ordered universe connect with the image offered by modern scientific cosmology? What challenges and opportunities does this difference present for contemporary Buddhist practitioners?

Depending on how you look at it, a fruitful dialogue can be established or none at all. At an astronomical level, it seems difficult: they tell us that modern physics proposes an outer space empty of life and values, impossible to reconcile with the Buddhist vision of an overpopulated and moral universe. We have been looking for links between Buddhism and physics or neuroscience for a long time, but I would say that there is more potential in Darwinian biology, as it describes a process analogous to that of karma and rebirth. Sentient beings are the way we are because of the actions of our evolutionary ancestors, who have determined our psycho-physical structure down to the smallest detail. Sentient life emerges, evolves and thrives through greed (Lobha) and aversion (Dosa) of beings undergoing a process of selecting survivors who manage to transmit their genes and, in many cases, impose themselves on their competitors. It's intriguing what it means, in this framework, that the Buddhist monk doesn't reproduce! He embraces radical non-aggressiveness and renounces the sexual desire that is behind his birth as a human being, but also, in Longue Durée, the fact that it has a head, a sternum, an opposable thumb... Introduce the concept of ignorance (Moha) is more complicated by its religious or evaluative nuance, but it is obvious that, from a Buddhist point of view, where aversion and greed, that fuel of sentient life, multiply, there is ignorance that allows its indefinite continuity.

I think that Buddhism and science can dialogue and find deep affinities. Of course, if we examine ancient Buddhist cosmology in detail, we will locate blatant ahistoricity, anthropocentrism, androcentrism (or direct misogyny), indocentrism, and even brushstrokes of casteism. It is a worldview created by humans and for humans, but this, rather than supposing an objection to this particular cosmology, should make us reflect on the limits of all cosmologies and what we expect from them.

—————————

Daniel Millet Gil has a law degree from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and has a master's degree and a doctorate in Buddhist Studies from the Center for Buddhist Studies of the University of Hong Kong. He received the Tung Lin Kok Yuen Award for Excellence in Buddhist Studies (2018-2019). He is a regular editor and author of the web platform Buddhistdoor in Spanish, as well as founder and president of the Dharma-Gaia Foundation (FDG), a non-profit organization dedicated to the academic teaching and dissemination of Buddhism in Spanish-speaking countries. This foundation also promotes and sponsors the Catalan Buddhist Film Festival. In addition, Millet serves as co-director of the Buddhist Studies program at the Fundació Universitat Rovira i Virgili (FURV), a joint initiative between the FDG and the FURV. In the editorial field, he manages both Editorial Dharma-Gaia and Editorial Unalome. He has published numerous articles and essays in academic and popular journals, which are available in his Academia.edu profile: https://hku-hk.academia.edu/DanielMillet