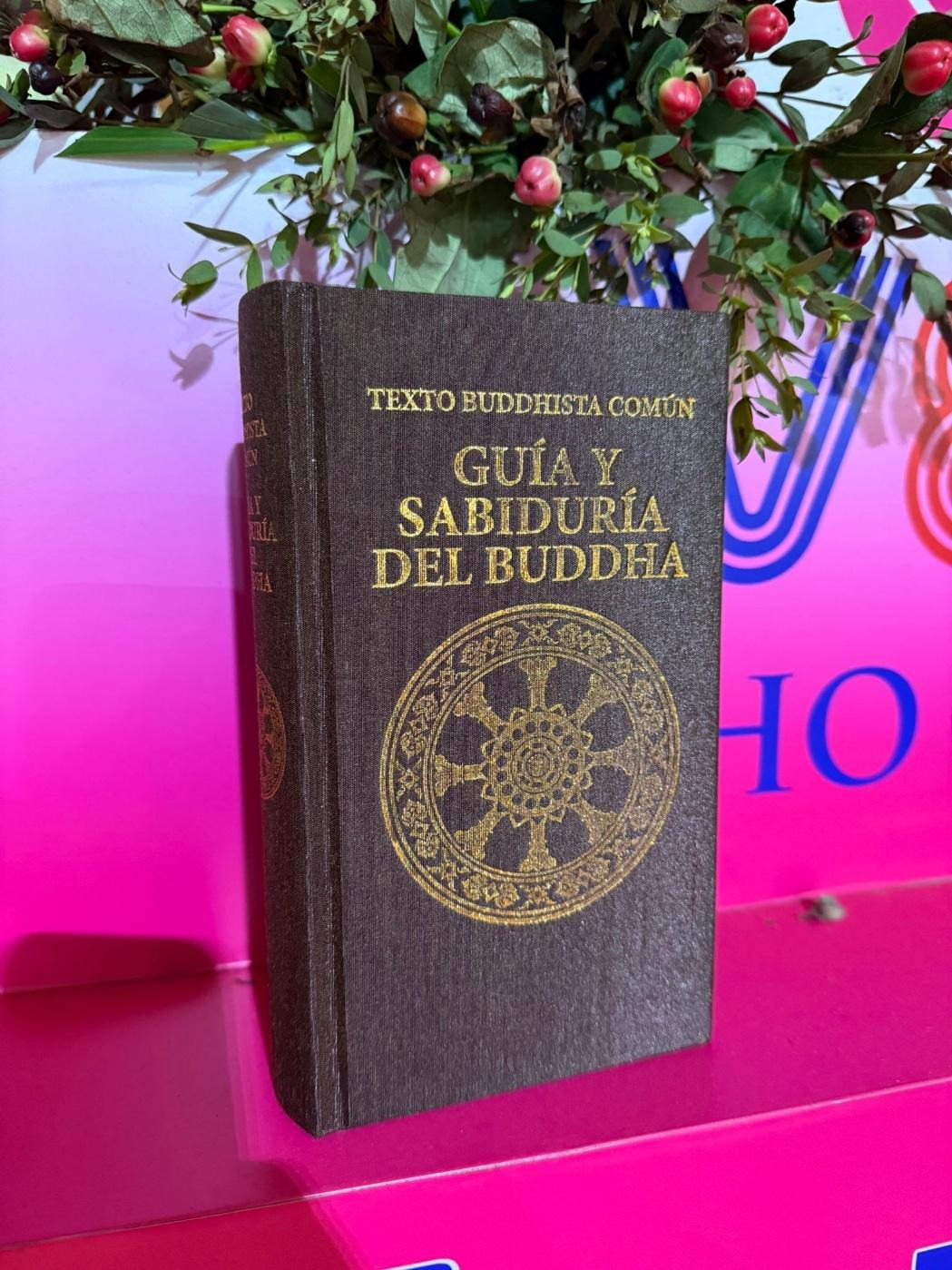

It is a pleasure for me to be able to present, through this brief synopsis, the anthological collection of Buddhist teachings collected in the book entitled: Common Buddhist text. The Buddha's guidance and wisdom. The fabulous monograph that I review here, with a luxurious binding, enhanced by the magnificent touch of its Japanese silk upholstery and gold print, reflects the solemn effort it has taken to have such a work in our language today.

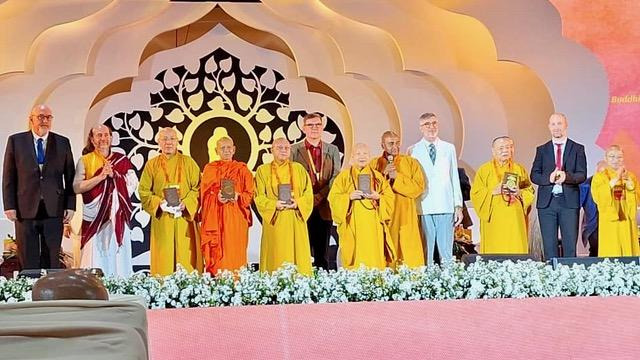

Throughout its seven hundred and five pages, we can take a fascinating journey that will take us through different translations of some of the most important texts in the history of Buddhism. The volume translated completely neatly into Spanish was presented last May 7, 2025 in Vietnam, in Ho Chi Minh City, on the occasion of the International Celebration of Vesak, an annual commemorative day in which the international Buddhist community remembers the Buddha (Gautama) during the first full moon of May. In addition, the work was also highlighted on May 10 in Bangkok, at the UN headquarters in Asia/Pacific, because it was printed in Thailand, and, in addition, because it was a project of International Council for the Day of Vesak, body that holds the status of consultative body of the United Nations Economic and Social Council.

Technical characteristics that make it a unique work in our language

Anyone who is interested in approaching Buddhism, in any of the multiple aspects that this religion covers, should know that they will not find, until now, such a compendium of Buddhist scriptures translated into Spanish anywhere else. From a technical point of view, the volume required the hard work of eleven specialists in the field, who have contributed not only to the translation of the primary sources, but also to the coordination of a common glossary of Buddhist terminology in Spanish (annexes). A glossary has been prepared in our language that includes the main terminology of the different languages necessary for the translation of Buddhist texts. This feat requires us to be as if not fair and to generously value the great effort and merit of the work done. Even more, the work shows the great effort made, given that in addition to doctrinal supervision and adaptation to the different language regions of Spanish (North America, the Caribbean, the Andes and the Southern Cone), a considerable stylistic and layout edition has been made, taking into account that we are talking about a work that brings us hundreds of pages, in which different texts and narratives of the Buddhist message, transmitted for centuries in different territories of Asia, are adapted.

The content of the book is divided into the following sections:

Introductions: different relevant aspects of the unification of translational criteria are explained, as well as the orthotypographic style used, in addition to offering valuable explanations about the different Buddhist trends and literary aspects covered.

1. FIRST PART: About the Buddha (Gautama). Two sections are presented: 1.1. The life of the historical Buddha, based on his best-known (mainly hagiographic) biography, the Sanskrit work of Aśvaghoṣa (2nd century AD). C.) and 1.2. The different perspectives of the three great Buddhist branches (Theravāda; Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna) on his figure.

2. SECOND PART: It focuses on Dharma, exposing some of the most important aspects of Buddhist teachings, based on the new interpretations of different scholastic records, such as those of the (2.3) Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna schools; as well as on their respective interpretations of society and human relationships (2.4). Also, in this same section, the translation and exposition of Buddhist scriptures from these three major branches continues to present the idiosyncrasy of human existence (2.5), as well as the Buddhist path: its practice (2.6), always focusing on the primary texts of the three great Buddhist currents: (theravāda, mahāyāna and vajrayāna). Successive chapters address the ethical message transmitted by the many followers of the Buddha, over time (2.7), finally focusing on three intrinsically related aspects in the life of every self-respecting Buddhist practitioner: meditation (2.8), wisdom (pragmatic, we will add; that which gives rise to or leads to ultimate liberation, of Dukkha) (2.9), as well as, the objectives of Buddhism (2.10).

3. THIRD PART: This last section of the magnificent collection of teachings and history of Buddhism results in the analysis of records related to the Buddhist community, using testimonies collected from multiple and very diverse primary sources, which affect the experiential experiences and, by their very religious and spiritual value, of great figures in the history of Buddhism, whether lay people (3.11) or renouncing (3.12).

4. APPENDICES: From my own experience I will say that it is not at all easy to unify terms in Spanish when translating a Buddhist text, which normally requires a paradigmatic-social structure that supports the semantic value of the words we are translating. In other words, context is something that is inevitably lost in any translation. That is where the great value of the final glossary that this work offers us lies. If we also consider that this collection has been compiled from primary sources in Pali, Sanskrit, Classical Chinese, as well as Tibetan, we can see, even more than the background work carried out, it has required a great collective effort. From it, this pioneering work has emerged in our language, which, as I say, fully retains the content of many of the most fundamental teachings, and therefore, that everyone, interested in Buddhism, should know; not focusing on a particular perspective of a Buddhist school, but quite the contrary, embracing with great success, I think, the dynamism and heterogeneity that precisely characterize that great complex religious phenomenon that we encompass as 'Buddhism'. Which is no longer merely part of the collective and therefore social consciousness of Asia, but is already part, and increasingly, thanks to this type of initiative, of the valuable humanistic knowledge of many people outside their place of origin.

Examples of the great translational value of this collection

Just to give the reader context to the difficulty of the work carried out, we will show below an example of a certainly complex translation from classical Chinese into our language. Anyone with some knowledge of research, of course, can contrast and, therefore, use this work as a study guide, which seems to me to be one of the most remarkable and valuable points that this volume contributes to for the Spanish-speaking reader. The work facilitates the possibility of using the translations of the primary sources used, as an angular essay to contrast and study the languages of Buddhism. Since primary sources are cited at all times, they can use these translations for the study and even academic verification of different historical aspects in the transmission of Buddhism. A good example of philological work —which I think can be of great help in the study of future Spanish speakers interested in Buddhist studies—can be seen in p.152-153, where the “Epitets and qualities of the Buddha” (T1488.24.1051b1-b16) are translated, an excerpt from a classical Chinese translation of the Writing the moral precepts of a lay Buddhist (T1488.24), carried out in the fourth century of our era by the monk Dharmakṣema (385-433 CE).

- The Tathāgata as, “Honorable Without Par” is the name of the name (T1488.24.1051b5).

- The Tathāgata as, “As the Buddha has gone through the stage of preparation to the unsurpassed perfect Awakening”, is known as the Tathāgata, “The So Come” (T1488.24.1051b9).

- Ar (a) hant (usually transliterated as) “the deserving one (T1488.24.1051b9). The contextual meaning of this title in ancient India is aptly explained in our language to refer to religious leaders who considered themselves deserving of different offerings (Arahati, From the Vedic Arhati, also related to the verb Agghati: which is “worthy or deserving”). When choosing the etymological translation for this type of phonetic transliteration, we will also point to archaic ones, prior to the unification of Buddhist terminology into classical Chinese, or to the “modern” criterion established by Xuán Zàng (602-664).

- “Since it has awakened to both levels of truth, to conventional truth and to ultimate truth, it is called Perfect and Fully Awake” (T1488.24.1051b10). Here again, the translator demonstrates his expertise and knowledge of the disparate way of transliterating the sound of Indian terminology. Here it would have been easy to err by interpreting literally as “The Buddha of the Three Light Qualities”; which would not have been correct, since here, superbly supplanted by the translator, reference is being made explicitly to the phonetics of the Indian concept of samyaksabuddha (as is the case in the case of samyaksabodhi ().

- “One who is complete in knowledge and conduct”, modified. Name of the name (T1488.24.1051b11). I consider that here the translation —as happens to me personally on many occasions too, especially when I focus (never better said) on interpreting Buddhism into Spanish— could have come a little closer to the meaning of the primary source, if I had said something like: “The one who Embodies the Light (of wisdom) (Vidyācaraṇasapanna)”, since he has realized the Three Knowledge (tevijjā) and has perfected himself, exercising the practice of meditation and preserving the purity of moral precepts (modified).

- “Since he will never be reborn in any form of existence, he is called the Sugata, “The One Who Has Started Well” (T1488.24.1051B12). Once again, the translator adopts an etymological position that brings the reader closer to the historical context, and, therefore, to the cultural meaning of the Indian concept, which is also indispensable when it comes to understanding what characters were chosen by the first translators of Buddhist texts.

- “Since he has full knowledge of the two worlds, the world of living beings and the physical world he knows, he is called “The knower of the worlds” (T1488.24.1051b13). Here the translation of the title mentions the meaning of the Indian concept lokavidū, although it does not recognize the figurative meaning of the second stratum mentioned, which is an allegory not of the “physical world” but of the highest spiritual stratum in the Buddhist worldview: the worlds of the Buddhas (= buddhakṣetra).

- “Unsurpassed leader of people who must be trained” (T1488.24.1051b14). Here again, the editor has perpetuated the etymological connotation of the equivalent Indian concept, purusadamyasārathi, which, as I review here, helps us to study the context and meaning of these titles, in India. Having pointed out the Indian terms in notes would have further contributed to the study of the primary sources, even if it had perhaps excessively loaded the didactic content for the profane reader.

- “Master of gods and humans” is (T1488.24.1051b15).

- “Bhagavā”, “The Blessed One”. Here the primary source indicates that “he is called for that reason, Buddha” (T1488.24.1051b16). The last epithet that breaks down in this list includes one of the names that I personally consider to be one of the oldest epithets of the Buddha (Villamor, 2024: n.21). Bhagavant, (literally “He who bears or possesses Bliss”) as such (T1488.24.1051b20); can be compared a few lines below.

To end this review

I fully understand the difficulty and great work done by the translators and editors who have made it possible for this unique collection of the Buddha's teachings to be in our language today. On a personal level, I have missed a greater historical context and notation on different concepts, which would have overloaded the reading of a work that seeks to bring the most memorable Buddhist teachings closer to any type of reader, not just the academic. The attempt to explain each term in detail would have required making this work, already extensive in itself, an authentic encyclopedia of Buddhism in our language. Objective from which, personally, I do not consider that the authors have fallen so far away. I sincerely hope that the work will more than achieve its pretensions and will bring the Spanish-speaking reader closer to the Guide and Wisdom of the Buddha. Hopefully it will also help new generations of scholars from Hispanic countries to join their conscientious study, to which, without a doubt, this work provides not a 'grain of rice'but a great light, for the future.

Repository of Buddhist Scriptures in Classical Chinese

(SAT) Daizōkyō Text Database (2018). The first time you are here to visit us. Department of Indian Philosophy and Buddhist Studies, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology University of Tokyo. https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Cited bibliography:

Villamor, E. (2023a). Transformation of Buddhist thought and the influence of jātaka fables on the Uji Shūi Monogatari [Doctoral thesis, University of Salamanca].

Villamor, E. (2023b). “Translation of Buddhist texts: a historical, philosophical and philological approach - Old challenges and new challenges posed by their interpretation, taking as a reference example the Prajñāpāramitā-hrṣdaya-sūtra”. CLINA Interdisciplinary Journal of Translation, Interpretation and Intercultural Communication, 8 (2), 107—133. https://doi.org/10.14201/clina202282107133

Villamor, E. (2024). “Did the Buddha Teach to Be Called “Buddha”? Focusing on the Meaning of Brāhmaṇa and How Buddhist Authors (re) Formulated His Words to Praise Him”. Religions, 15 (11), 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15111315

You can download the non-printable digital version of the Common Buddhist Text through the following link: Common Buddhist Text

EFRAÍN VILLAMOR HERRERO (Teikyo University, Japan)

Efrain Villamor Herrero (Bilbao, 1986). Degree in Japanese philology (2012-2016), Doctor (University of Salamanca, 2023). His main fields of study are Indian Buddhism and its influence on Japanese thought. Member of the Recognized Research Group, EURASIA HUMANISM (USAL), the Society for the Study of Pali and Buddhist Culture (Japan) and The Japanese Association of Indian and Buddhist Studies; among other academic associations for the study and dissemination of Indian and Japanese Buddhism. (Instagram: I study Buddhism)