introduction

Buddhism offers a way to free oneself from the wheel of deaths and births that follow one another in a seemingly endless sequence. The Buddha had stated that his teachings were aimed at four groups: lay women, nuns, lay men and monks. He never denied the ability of women to achieve enlightenment and the heightened state of consciousness of Arahant. Nor did he refuse to teach them the Dharma. However, the admission of women to the monastic community was neither immediate nor unhindered.

It is difficult to know with complete certainty which texts or portions of texts reflect what the Buddha actually said and what was later interspersed by misogynistic scribes. Nor can we expect total coincidence in the texts available today about the women and men who are protagonists and managers of Buddhism, but we can find stories that reflect how certain events were perceived and valued at the time when they occurred. Taking into account the above, the main contribution of Mahāprajāpatī, the foster mother of Buddha Siddhartha Gáutama, in the expansion of the Sangha or Buddhist community.

Mahāprajāpatī, second wife of Suddhodhana

Siddhartha Gáutama, who would later be known as the Buddha, was born as a prince of the Shakya clan in Kapilavastu, probably in the 6th century AD. He was the son of King Śuddhodana and Queen Mahamaya, who died seven days after giving birth to him. His sister Mahāprajāpatī took care of little Siddhartha.

Queen Mahamaya of the Sakyas clan was born into a family Kshátriya or of the ruling caste in Devadaha, near the town of Kapilavastu where the Buddha was raised. He had six other sisters, including Mahāprajāpatī Gáutami. Both married King Śuddhodana of Kapilavastu and thus became their two main queens, with Mahamaya being the one who prevailed. Queen Mahamaya gave birth to Siddhartha Gáutama, who would later be known as the Buddha and died a week later. His sister Mahāprajāpatī took care of the boy Siddhartha and raised him as her own. He was not the only son he raised, since, as Sudhodhana's second wife, Mahāprajāpatī had given birth to her daughter Sundarinanda and son Nanda, who would eventually adopt monastic life as would Siddhartha.

Mahāprajāpatī as a lay practitioner

We will skip the well-known story of Siddhartha's life as a young prince protected from the evils of life and his resignation from palatial life at the age of twenty-nine, after learning about the existence of suffering in the world and committing himself to finding a solution to it. We will also skip the six years he spent in the woods until we had an experience of enlightening consciousness in which he found the solution he was looking for.

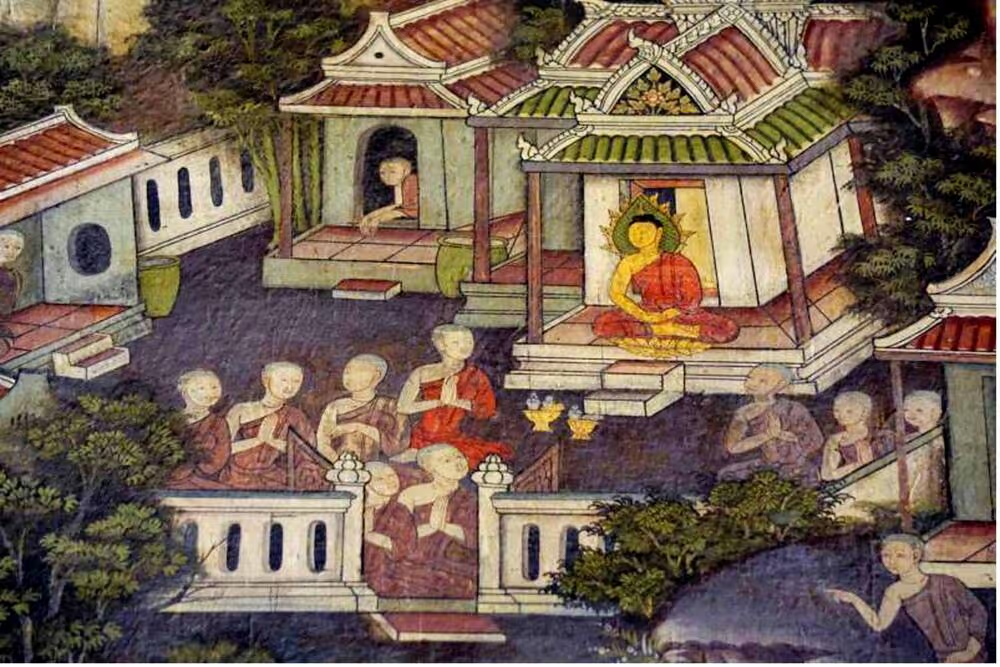

We will be located approximately six years after the Buddha's experience of enlightenment, that is, about twelve years after he left the palace and his life as a prince. The Buddha arrived in Kapilavastu with a group of five hundred (symbolic number to designate a large number) male followers and thus visited for the first time his father Śuddhodana, his mother Mahāprajāpatī, his main wife Yashódara, his son Ráhula and other relatives and inhabitants of the palace where he had grown up.

The Buddha's relatives begged him in vain to become the prince of Kapilavastu again, since King Suddhodhana did not yet have an heir to the throne. Instead, he dedicated himself to preaching the Dharma to his relatives and other inhabitants of the kingdom, who became his first lay disciples. Mahāprajāpatī managed to penetrate the teachings to such depth that he attained a first level of enlightenment of consciousness called Sotapanna. (Later I would achieve the more advanced stages of Sakadagami, Anagami and Arahant.) Thus, she became the first woman in Kapilavastu to become a lay woman who followed the Buddha. Many men in the region were attracted to the Buddha's teaching and seized the opportunity. Inspired by their queen turned disciple of their son, the women in the palace also expressed their desire to learn the Dharma that their husbands and sons were receiving. Thanks to the intercession of Mahāprajāpatī, the Buddha agreed to give them instruction, and women soon joined the ranks of the lay sangha.

Mahāprajāpatī as a monastic practitioner

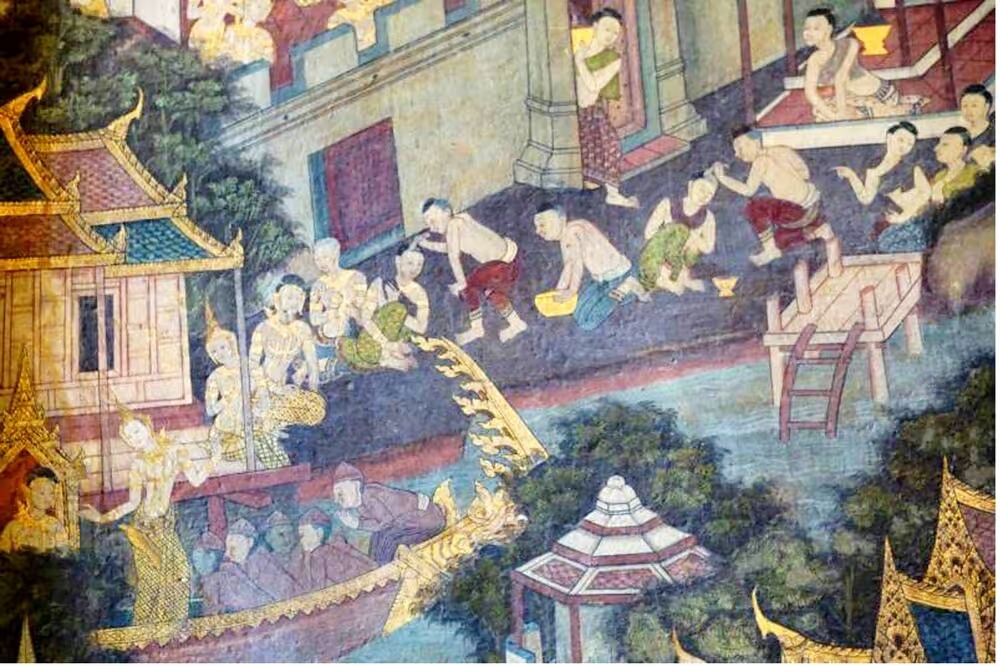

The Buddha made a second visit to Kapilavastu five years after his first visit, that is, seventeen years after he renounced his life as a prince. His father had died without leaving an heir. Siddhartha's decision to relinquish the throne of Kapilavastu at the age of twenty-nine had caused shock and disturbance, not only in the family environment but also in the political and social spheres of the kingdom. Since their departure, little by little, hundreds of Sakya men have been leaving their homes in Kapilavastu to become monks under the leadership of the Buddha. The city would be vulnerable to foreign conquest, which would eventually have to happen with the invasion of the nearby kingdom of Kosala. Many women in the palace, both from the royal family and the concubines and servants, were in a state similar to widowhood, since their respective husbands had joined the order of the Buddha. Several, including Mahāprajāpatī, had male children who in turn had become monks.

For the lay women of Kapilavastu, it was no longer a realistic option to go on with their former lives as lay women, now without husbands. They had acquired a condition similar to widowhood, without the traditional patriarchal social and legal structures that in another era would have afforded them protection. The Sangha or group of followers of the Buddha could well have served as a way to obtain protection similar to that of life in a traditional family, which was no longer available to them. They decided, therefore, to be ordained as nuns in the Dharma, however, as they had a few years ago, they had a sincere desire to deepen the teachings that the Buddha had imparted to them during their first visit to Kapilavastu. Again, they asked their newly widowed queen Mahāprajāpatī for support and leadership to intercede for them, who would not only give them the requested support but would join them in seeking monastic ordination.

Mahāprajāpatī asked the Buddha for permission to be ordained, in her own name and in the name of other lay women. Faced with the Buddha's first refusal, Mahāprajāpatī submitted his request twice more and the Buddha refused permission again, that is, a total of three times. As an alternative, she suggested that women lead a life of renouncing and practicing Dharma within their own homes, a difficult situation for women whose husbands had abandoned home life.

There are several possible reasons why the Buddha initially refused to accept a female monastic order, but one stands out. Since celibacy was a requirement for a monastic life, she was perhaps concerned that this requirement would be transgressed: most of the women who followed Mahāprajāpatī had ex-husbands who had become monks, and this circumstance could be tempting for ex-partners to get together again. The Buddha was always concerned with keeping the female and male sectors separate, since the Sangha had to maintain an exemplary behavior before its benefactors of the nobility who, among other supports in exchange for receiving teachings, lent their palaces to the monks where they stayed during the rainy seasons.

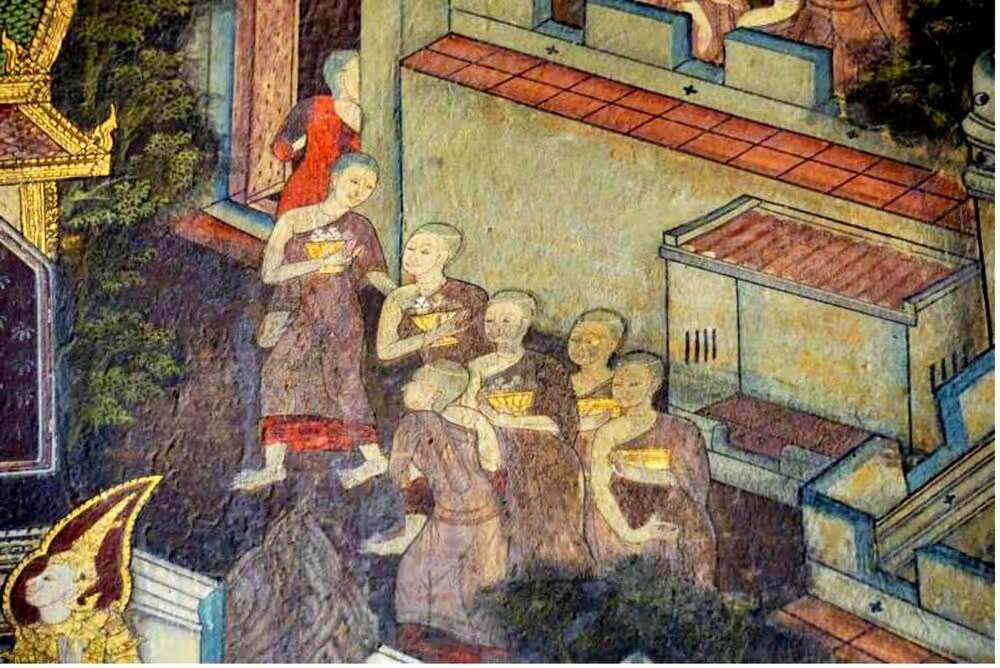

By then Mahāprajāpatī already had five hundred lay followers, a symbolic number as mentioned above. Neither Mahāprajāpatī nor her followers were discouraged by the Buddha's three denials: they shaved their heads, wore simple robes and undertook a long and difficult journey on foot from Kapilavastu to Vaishali to obtain ordination permission.

They traveled more than four hundred kilometers to find the Buddha with his male sangha. Ananda, a family member and assistant to the Buddha, observed them after their long journey and asked them why they had undertaken such a long and arduous journey. Mahāprajāpatī explained that in vain they had asked the Buddha for permission to enter the monastic order three times in vain. Ananda decided to intercede for women and so she gave the Buddha three reminders: (1) that previous Buddhas had ordained women, (2) that women had the same spiritual capacity as men to become Arahants, (3) that his mother Mahāprajāpatī had raised and cared for him and therefore the Buddha owed her an inescapable debt.

The inclusion of women as nuns in the sangha

(A) The set of eight rules

The Buddha finally accepted the inclusion of women in the monastic order, although under certain conditions. The Buddha is credited with pronouncing a set of eight rules called Gurudharma that the nuns should follow. Below is a translation of these rules as written in English by Ann Heirman:

(1) Even if a nun has a hundred years of monastic training, she must stand up and offer a bow to a newly ordained monk.

(2) A nun cannot reprimand a monk by telling him that he has committed a fault.

(3) A nun cannot punish or admonish a monk, but a monk can admonish a nun.

(4) After going through a trial period of two years, the ordination of a nun must be celebrated in both the female and male orders.

(5) If a nun has committed a fault that merits temporary exclusion, she must perform penance in both female and male orders.

(6) Every two weeks, the nuns must ask the monks for instruction.

(7) Nuns cannot spend rainy season retreats during the summer in places where there are no monks.

(8) At the end of the rainy season retreat, each nun must participate in a ceremony in which the other nuns and monks are invited to point out the faults they have incurred, whether they are misseen, heard or suspected.

The eight rules could well have been a way to mitigate in advance an opposition to the inclusion of women in the monastic order by the male community, which would be a reflection of the misogynistic beliefs of the time in India and not typical of Buddhism. Given the patriarchal culture and institutions surrounding the Buddha, he somehow had to ensure that monks accepted the inclusion of nuns. However, as much as the Buddha may consider it prudent to give up some ground to the customs of his time, these rules are clearly discriminatory in our contemporary eyes.

(B) The Future of Dharma

In addition to the set of eight rules, the Buddha is also attributed a prophetic commentary on the future of Dharma if women are accepted to the monastic order. The Buddha had told Ananda that the Dharma would last a thousand years, but since women would now receive their monastic ordination, the Dharma would only last five hundred years, since the female presence would be like a plague that wipes out a crop. In other words, the number of years that the teachings would last would be cut in half.

At first glance, it might seem like a disparaging comment for the presence of women in the monastic order. Taken literally, a prediction is attributed to the Buddha that has obviously not been fulfilled. However, there are other ways to interpret these proclamations attributed to the Buddha. Sulak Sivaraksa says that thanks to the establishment of the female order, it would only take half of years to establish Dharma in the world. In other words, doubling the number of followers of the Buddha, it would only take half the time to transmit the Dharma over several generations and in different lands.

In support of Sivaraksa's interpretation, it must be remembered that according to Buddhism, everything inevitably changes. A cultivated field would sooner or later become barren and, of course, a pest would accelerate its transformation. There are no fixed and eternal essences; even the teachings of Siddhartha Gáutama Buddha of the present age are not permanent. By establishing a probably symbolic period of five hundred years, that is, half a thousand years, the Buddha perhaps asserted that the Dharma he taught would not last eternally either. In the same way, the teachings of the previous Buddhas were not eternal, since each Buddha had to adapt his teachings to the spaces and times of his respective time. In this way, the goal that the Buddha had set for himself—to achieve as many beings as possible attain enlightenment—would accelerate with twice the number of followers.

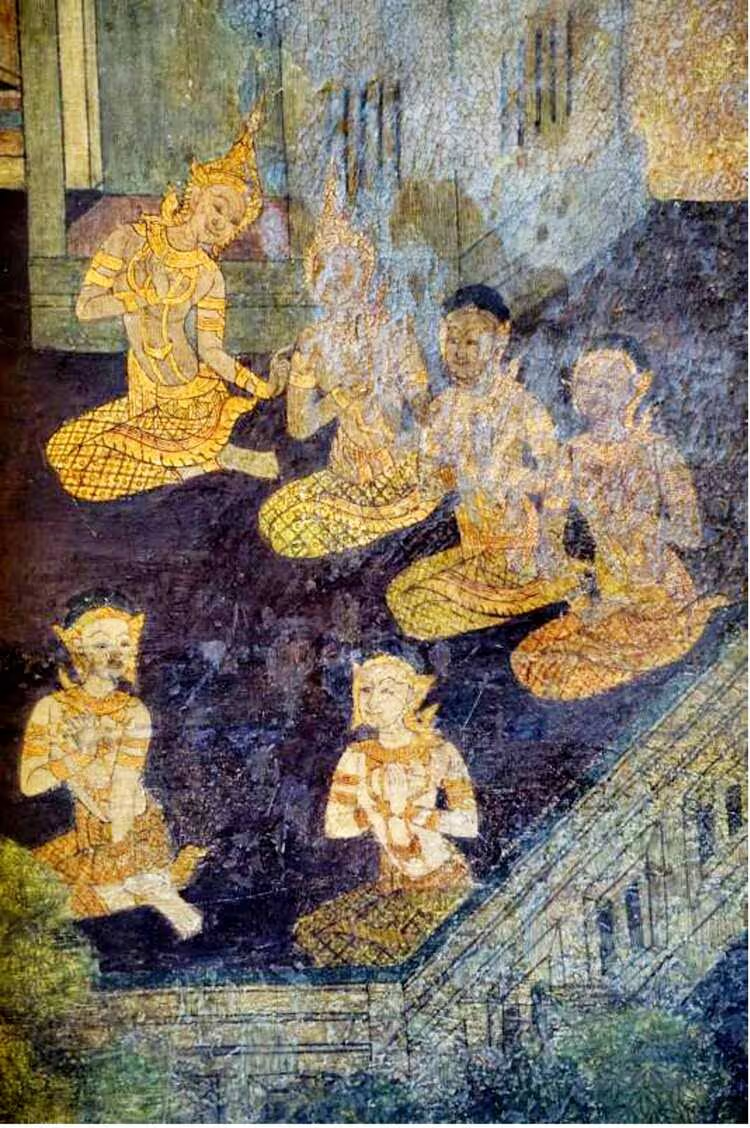

When the Buddha approved the admission of women to the monastic community, Mahāprajāpatī became the leader and maternal figure for both nuns and lay women. It is said that Mahāprajāpatī lived a very long life; there even came a time when he went to the Buddha at an advanced age to tell him that the right thing to do was for a mother to die before her children. The Buddha nodded and so, a few months before the Parinirvana or death of her son, Mahāprajāpatī was the first disciple to enter the state of Nirvana upon death. It is also said that, by their own will, her five hundred followers also reached the Nirvana when she died the same day as her teacher.

Conclusions

As Sivaraksa rightly points out, both Mahāprajāpatī Gótami and her five hundred female followers were completely sure that, like men, they had the capacity to become Arahants and that is why they did not faint in their insistence on belonging to the monastic order established by the Buddha. In this sense, Mahāprajāpatī and the first order of nuns are an example of tenacity in the Dharma.

The Buddha had stated that his teachings were aimed at four groups: lay women, nuns, lay men and monks. Mahāprajāpatī played an essential role in making these four groups of people part of his sangha or community of followers. Since Buddhism has gone around the world and is present on every continent today, it can be inferred that the female participation of lay women and nuns significantly increased the presence of Buddhism. Indeed, Mahāprajāpatī doubled the number of followers of the Buddha and opened the doors of Dharma to all women who wanted to learn and practice it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Analayo, Bhikkhu (2013). The Revival of the Bhikkhunī Order and the Decline of the Sasana. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 20, 110-193. Available in https://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/files/2013/06/Anaalayo-bhikkhuni-revival1.pdf

Analayo, Bhikkhu (2022). Daughters of the Buddha: Teachings by Ancient Indian Women. Somerville, Massachusetts, USA: Wisdom.

Garling, W. (2016). Stars at Dawn: Forgotten Stories of Women in the Buddha's Life. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Shambhala.

Garling, W. (2021). The Woman Who Raised the Buddha: The Extraordinary Life of Mahaprajapati. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Shambhala.

Heirman, A. (2011). Buddhist Nuns: Between Past and Present. Number 58, 603—631. Available in https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/55700974.pdf

Ohnuma, R. (2006). Debt to the mother: A Neglected Aspect of the Founding of the Buddhist Nuns' Order. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 74, 861-901. Available in https://www.academia.edu/10975640/Debt_to_the_Mother_A_Neglected_Aspect_of_the_Founding_of_the_Buddhist_Nuns_Order

Ríos, M.E. (2017), Aesthetics of Abandonment: The Retreat of Buddhist Nuns. Lu. Journal of Religious Sciences 22, 343-357. Available in https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ILUR/article/view/57420/51724

Sivaraksa, S. (1992). Seeds of Peace: A Buddhist Vision for Renewing Society. Berkeley, California, USA: Parallax. Available in https://archive.org/details/seedsofpeacebudd00sula

Katherine V. Massis-Iverson

The author is a retired professor at the University of Costa Rica in San José, Costa Rica. For several years as an active teacher, she taught introductory philosophy courses at the School of General Studies, as well as courses in ethics and Hindu and Buddhist thought at the School of Philosophy of that institution. Some of his work can be found at https://ucr.academia.edu/KatherineMas%C3%ADsIverson