Christian Zen emerged in the mid-20th century, when several Christian religious, mainly Catholics, began to adopt Zen Buddhist methods to revitalize their contemplative practice. This movement has spread to Europe, America and several countries in Asia, through courses, retreats and publications. A prominent example of this integration is that of the Jesuit monk Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle, who, in Japan, was a pioneer in combining the practice of Zen with Christianity. Enomiya-Lassalle led numerous Christians on Zen meditation retreats and promoted dialogue between the two traditions. However, the development of Christian Zen has not been without controversy, facing criticism both from the Christian and Buddhist spheres. This article critically analyzes the impact of Christian Zen on Catholic spirituality, exploring its benefits, doctrinal tensions and the questions it poses for interreligious dialogue.

Supporters of Christian Zen argue that the adoption of Zen is justified by its effectiveness as a tool to deepen the Christian contemplative experience and improve understanding of the Scriptures. However, Christian theologians have reacted with concern, pointing to possible dogmatic transgressions, while Buddhist scholars question the legitimacy of separating Zen meditation from its Buddhist context. For example, theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar criticized various forms of syncretism, such as Christian Zen, considering that these practices dilute identity and compromise the integrity of the Christian faith [i]. On the other hand, Zen teachers, such as Shunryu Suzuki, have warned that separating Zen from its Buddhist context can distort its essence and distort its true purpose [ii]. This tension between traditions has generated a rich debate about the nature of spiritual experience and the limits of interreligious dialogue.

The debate on Christian Zen raises fundamental questions: Is Zen practiced in this context the same one that has its ancient roots in India and developed in China and Japan? Can Zen be uprooted from its Buddhist foundations without losing its essence? Is the practice of Zen compatible with prayer and Christian spirituality? How is the incorporation of Zen meditation into Christian life theologically justified? These issues transcend mere academics, since they profoundly affect the spiritual practice of thousands of Christians who have integrated elements of Zen into their lives, facing the challenge of harmonizing both traditions in an authentic and coherent way.

The understanding of Zen in Christian Zen differs significantly from the historical Chan and Zen tradition. While traditional Zen is deeply rooted in Mahāyāna Buddhism, with its specific doctrines and practices, Christian Zen presents Zen as a universal and transreligious methodology, devoid of a Buddhist doctrinal content. This interpretation finds its initial basis in ideas that emerged during the Meiji reform of Japanese Buddhism, a period of profound transformation and westernization that marked the first step in the way in which Zen was presented to the Western world.

A crucial aspect in the development of Christian Zen was its connection with the Sanbōkyōdan school (now called Sanbō-Zen), especially through the teacher Yamada Kōun. This school, considered heterodox by traditional Japanese Zen, was unique in allowing Christians to practice Zen without abandoning their faith, and it even authorized some as Zen teachers.

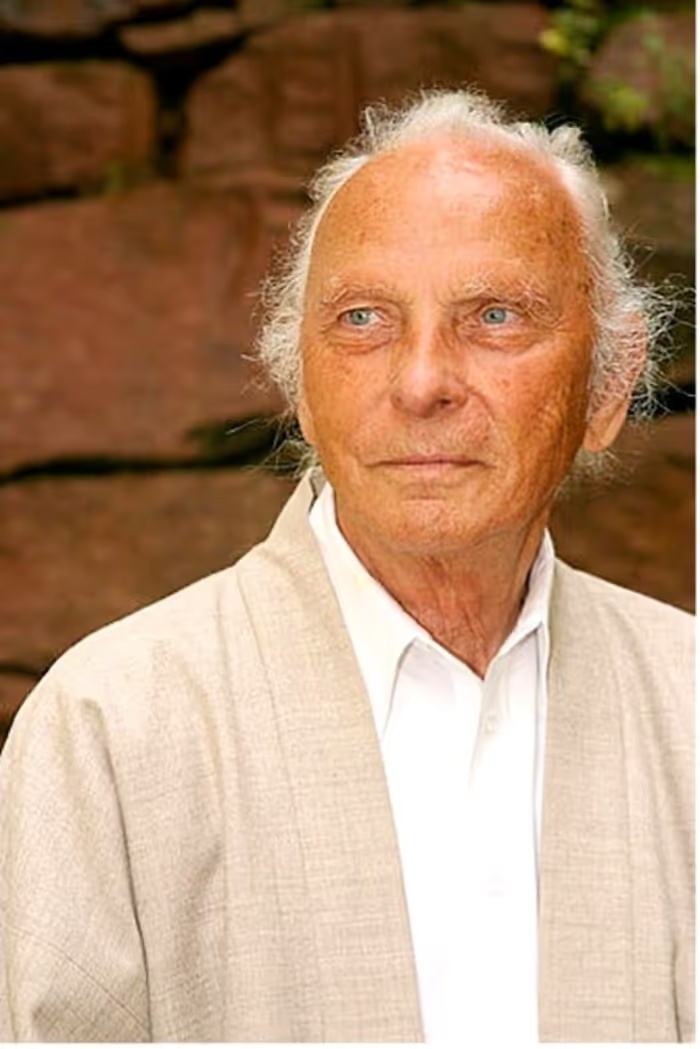

Among the Christians authorized as Zen teachers by Yamada Kōun are figures such as the Benedictine monk Willigis Jäger, who integrated these teachings into his monastic life. However, his teachings, which sought to combine Zen with Christianity, led him to be disciplined by the Catholic Church, which banned him from teaching publicly in his name. This unprecedented openness on the part of Yamada Kōun and the Sanbōkyōdan school constitutes an exception within traditional Japanese Zen, which generally does not seek to integrate other religions. The influence of Sanbōkyōdan was key to the rise of Christian Zen, although it also raised questions about the authenticity and legitimacy of this transmission. This universalist approach marked a model that has influenced the way in which Zen has adapted to the Christian and Western context, although it has not been adopted by traditional Zen schools.

The fundamental differences between Buddhism and Christianity present significant challenges for Christian Zen. Buddhism is a non-theistic tradition that emphasizes dependent origination —the teaching that all phenomena arise in dependence on causes and conditions—and the doctrine of no-self —which refers to the absence of a permanent, fixed, or independent “me” —In contrast, Christianity is based on belief in a personal and creative God, the existence of an immortal soul, and salvation as a gift of divine grace. These doctrinal differences are not superficial; on the contrary, they profoundly affect the very nature of the practice and its objectives. The tension between these worldviews has led to various attempts at reconciliation, some more successful than others, and it remains a topic of debate both theologically and practically.

The practice of meditation in Christian Zen also raises important questions. While traditional Christian contemplation is oriented towards the encounter with God and is rooted in Christian revelation, Zen meditation seeks to awaken to the true nature of reality according to Buddhist understanding. The attempt to reconcile these different approaches has led to interpretations that can distort both Zen and Christian traditions. Some practitioners have developed hybrid methods that attempt to maintain the integrity of both traditions, while others have opted for a clearer separation between practices.

The spiritual experiences of Zen (Kenshō) and Christian contemplation (mystical union) also have significant differences. Although they may share some phenomenological aspects, their contexts, interpretations and meanings are fundamentally different. El Kenshō is an experience of the Buddha's nature and non-duality, while Christian mystical union is a personal encounter with God facilitated by divine grace. This fundamental distinction has led to debates about the nature of religious experience and the possibility that similar experiences may have radically different interpretations depending on the religious context.

The impact of Christian Zen on Christian monastic life has been particularly notable. Numerous monasteries and convents have incorporated elements of Zen practice into their daily routine, from meditative posture to mindfulness in daily activities. This integration has led to a renewal of contemplative life in many religious communities, although it has also generated tensions with more traditional church authorities.

The training of Christian Zen teachers represents another controversial aspect of the movement. While some have received formal authorization from Japanese Zen teachers, others have developed their own interpretations and teaching methods. This diversity of approaches has enriched the movement, but it has also raised questions about the authenticity and legitimacy of the transmission.

Christian Zen has had a significant impact on contemporary Christian theology, especially in areas such as comparative mysticism and interreligious dialogue. It has contributed to greater openness to other spiritual traditions and has encouraged a profound reflection on the nature of religious experience. However, it has also raised concerns about syncretism and the possible dilution of Christian identity.

In the pastoral field, Christian Zen has provided practical tools for the spiritual renewal of many Christians. The simplicity and effectiveness of Zen meditation techniques have helped many to rediscover the contemplative dimension of their own tradition. However, this has also posed challenges in terms of adequate formation and spiritual accompaniment.

Christian Zen represents an attempt at practical interreligious dialogue, but it raises fundamental questions about the nature of religious experience and the possibility of transplanting spiritual practices between different traditions. Although some practitioners report benefits in their spiritual lives, the legitimacy of Christian Zen as a hybrid practice continues to be questioned by both Christian authorities and traditional Zen teachers.

In conclusion, the Zen of Christian Zen seems to be a modern reinterpretation that moves significantly away from traditional Zen. Although it may offer useful tools for some Christian practitioners, and there are voices within Buddhism and Christianity that recognize the value of this type of interfaith dialogue and hybrid practices, its theological foundation and its relationship with both religious traditions remains problematic.

The phenomenon of Christian Zen illustrates the challenges and complexities of contemporary interreligious dialogue, especially when it involves the adoption of practices between traditions with fundamentally different worldviews. Can this hybrid practice be an authentic bridge between religions, or does it risk diluting the spiritual identities it seeks to connect? Christian Zen invites us to reflect on the limits and possibilities of interreligious dialogue. How can we encourage hybrid practices that respect the integrity of original traditions while enriching our spirituality? This is a key challenge for religious dialogue in the 21st century.

*This text is based on a chapter of my own entitled “Christian Zen: A Critical Examination of the Use of Zen Among Catholics”, included in the second volume of the book Buddhist Studies in Latin America and Spain, a book that I co-published with Dr. Jaume Vallverdú. It was published by Publicacions URV in co-edition with the Dharma-Gaia Foundation on October 8, 2024. This work brings together research by leading specialists and analyzes the impact, evolution and practices of Buddhism in Spanish-speaking contexts. Divided into two volumes, the publication constitutes a valuable contribution to the study of Buddhism in Latin America and Spain, promoting interdisciplinary and interreligious dialogue. Both volumes are available in PDF format and can be downloaded free of charge through the following links First volume and Second volume.

Bibliography/Webgraphy

Baatz, U. (2019) “Why do Christians practice Zen?” , in E. J. Harris and J. O'Grady (eds. ), Meditation in Buddhist-Christian Encounter: A Critical Analysis, Sankt Ottlien: Eos Editions, pp. 145-195.

Carini, C. and Puglisi, R. (2015) “A Christian Zen Buddhism? Ritual intersections and symbolic exchanges in the Zendo Betania school in Argentina from an ethnographic perspective”, presentation XV Interschool Conference, Comodoro Rivadavia.

Enomiya-Lassalle, H.M. (1974) Zen Meditation for Christians, LaSalle: Open Court Publ.

Kōun, Yamada (2015). Zen: The Authentic Gate, Wisdom Publications.

Jager, W. (1987) The Way to Contemplation, New York: Paulist Press.

----------------------------------------------------------------

[i] In his work Truth is Symphonic: Aspects of Christian Pluralism (Truth is Symphonic: Aspects of Christian Pluralism), von Balthasar argues that Christianity must interact with other traditions, but without compromising its theological core or relativising the truth of Christ. Although it doesn't mention the Christian Zen specifically, their critical stance toward syncretism can be extrapolated to practices such as this one.

[ii] Shunryu Suzuki, in his book Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind (Zen mind, beginner's mind), emphasizes that Zen is rooted in the Buddhist tradition and that its practice cannot be separated from its spiritual and philosophical context without losing its essence. Suzuki stresses the importance of understanding Zen as an integral expression of Buddhism, beyond an isolated technique or philosophy.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Daniel Millet Gil has a law degree from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a master's degree and doctorate in Buddhist Studies from the Center for Buddhist Studies of the University of Hong Kong. Awarded the Tung Lin Kok Yuen Award for Excellence in Buddhist Studies (2018-2019). He is executive editor and regular contributor to the Buddhistdoor platform in Spanish and founder-president of the Dharma-Gaia Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to academic teaching and dissemination of Buddhism in Spanish-speaking countries. This foundation also promotes and sponsors the Catalan Buddhist Film Festival. In addition, Millet serves as co-director of the Buddhist Studies program at the Fundació Universitat Rovira i Virgili (FURV). In the editorial field, he manages both Editorial Dharma-Gaia and Editorial Unalome, both specialized in publishing translations of Buddhist texts. His numerous academic and popular publications are available at: https://hku-hk.academia.edu/DanielMillet