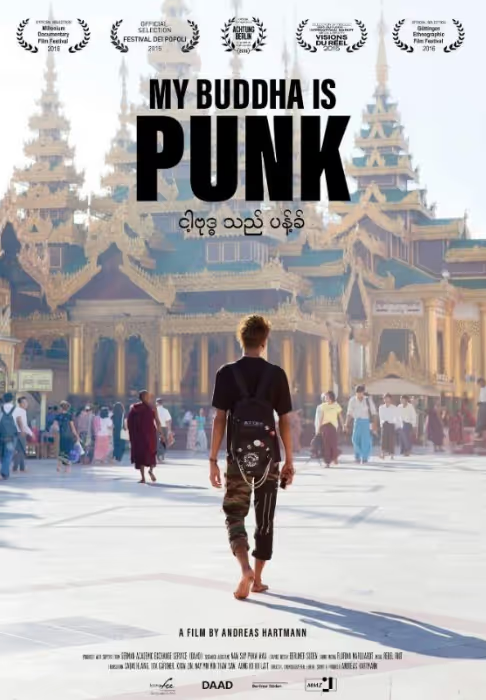

In the era of Gautama Buddha, approximately 2500 years ago, the concept of Human Rights had not yet been ratified as the standard of humanism. Just like today, then, numerous rights that we now believe to be essential were continuously violated, also in an unnoticed way. Gautama Buddha did not create a social revolution movement. Even so, he never accepted violence or the supremacy of any being, whether human or divine, so, of course, much less did he accept that someone should be discriminated against because they were different. The documentary film that I review here, My Buddha is Punk (2015) presents with great narrative accuracy and audacity the hopelessness and social anguish of Burma, a broken society, in which “Buddhist” fundamentalism has supported scandalous violations of human rights for years. The genocides committed against the Muslim minority of the Rohingya set up a group of young Buddhists with the purpose of publicizing such an atrocity, but, above all, what they consider to be true implications of Buddhism. Strangely enough, these young activists insist that punk is their only ”Buddha”. I think it goes without saying that in the time of Gautama Buddha, punk didn't exist. Now, as I indicate here, I very much doubt that the humanist thinking of the founder of Buddhism, his teachings and the story behind the Burmese punk movement in this documentary, have nothing to do with each other.

The photographic staging of the documentary is magnificent, even though I am not a specialist in the field, I consider myself a cinephile enough to be able to say so. The daily routine of its protagonist allows us to travel together with his ideals through different Buddhist temples and remote places in Burma. Their serene expression during meditative practice contrasts with their exacerbated features throughout the scenes that recount the frenzy with which they celebrate their concerts. His music, as well as his activism, also travels through the most rural areas of that country, with the mission of connecting with new generations and bringing them not only closer to his band, but also to his principles. The intense gaze of its protagonist, Kyaw Kyaw, thus appeals to reform Burmese society through the fusion of punk music together with his interpretation of Buddhist teachings.

Synopsis of this documentary

The documentary story of this filmography features the Burmese activist, Kyaw Kyaw, a member of the Burmese group classified in the rock-punk genre. They become known as The Rebel Riot. His intention is clear, to reveal himself before the established system and to highlight, through his music, the human rights violations that occur in his country. His motivation involves his interpretation of Buddhism, which seeks to detach himself from the rigid relationship that this religion maintains with the highest political spheres and the most deeply rooted traditions of its culture. The story is told from the point of view of these young people, who question the true meaning of Buddhism, expressing through punk the values that they consider to be truly universal.

The new generations represented in the documentary grew up in the era of the Burmese dictatorship. Perhaps for this reason, it seems that they find in punk a channeler in their personal search. They identify with this style of music and promote it as the spirit of the liberation movement that they themselves interpret as the authentic Buddhist message. According to public interviews given by the band's renowned leader, the Burmese punk movement, as an urban phenomenon, emerged in the 90s. In 2007, the protests led by certain sectors of monks, known as the “Saffron Revolution”, led to the punk phenomenon establishing itself as a standard of resistance,” says Kyaw Kyaw. The humanistic, democratic and Buddhist principles of their society are called into question by this group of reformers. Among the daily idiosyncrasy of the Burmese capital, Yangon, stands out the contrast between its daring punk outfits, with the more conservative clothing of the people who walk the streets. The skepticism towards individual liberties in their country emerges as part of the rebellion that these young people want to transmit, not only because of the ethnocentric vision most deeply rooted in their society, but because they precisely consider that it is far from the essence of the Buddhist message. The modern versus the traditional does not clash in this story as part of a generational struggle, but rather, it originates from a search for spiritual peace, from social activism. Together with the members of his band, Kyaw Kyaw tries to make the peoples of his land aware of the lack of democratic tools in their society, but above all of the constant violation of human rights resulting from the military dictatorship backed by the most staunch Buddhist orthodoxy.

Why is it necessary to publicize this story?

The support for recalcitrant hate speech from certain monastic-Buddhist sectors in Burma, against much more than just the social reputation of the Rohingya, supported the campaign of ethnic genocide carried out mainly by the country's military forces. According to the director of this documentary, Andreas Hartmann, his purpose in filming this documentary was to publicize the convulsive history of Burma, a country that, in 2011, after more than fifty years stained by the blood of a tenacious dictatorship, continues to suffer from the violation of human rights. According to data provided by the non-governmental organization dedicated to the research, defense and promotion of human rights, Human Rights Watch, the Rohingya ethnic minority in Burma has suffered from discrimination and relentless repression for decades. The Rohingya are a minority of Bengali and Muslim origin, who for the most part do not have national recognition (in 1982 the Burmese Civil Law denied their nationality). As stateless persons, they have suffered persecution, execution and discrimination for many years. The genocides against their ethnicity at the hands of Burmese military forces in recent years have garnered international media interest, although the conflict does not seem to have been completely resolved.

According to this organization, it is estimated that approximately one million Rohingya live together in camps in Bangladesh, where the vast majority of them took refuge after war crimes committed against their ethnic group, in Burma, during August 2017. Approximately 600,000 of these people have been disparaged because of their ethnicity, being confined to different concentration camps across this country. This disgrace is no stranger to fundamentalist orthodoxy, the political doctrine that is claimed to be “Buddhism”. The crux of the plot of this documentary is precisely a reflection on the true Buddhist message. His story reflects on whether fundamentalism could actually be considered authentic. ”Buddhism”.

From the Buddhist philosophical point of view

I don't know any Burmese monks in person. I know that Buddhism has been established as its religious pillar for centuries, and that, as is the case in the vast majority of Southeast Asian countries, its main aspect is ascribed to Theravāda Buddhism. However, because of my specialization and training in the field, in addition to the fact that I know enough people, I am aware that “habit does not make a monk”, not even within the Buddhist context. The ontological analysis of Gautama Buddha was based precisely on this, in the fact that what really matters is what the heart houses. From the point of view of Buddhist philosophy, how can we interpret the message of this documentary? Well, although I don't think it's necessary to make the spoiler, since answering this question does not require an exquisite knowledge of Buddhist teachings; I would like to briefly state here some arguments for reflection.

If the mental process (Sangkhāra) of harboring hatred or rejection (Dosa) (without even stopping to discuss whether this could be justified towards a certain type of ethnicity) would be useful to reverse (Pathiloma) the causes of suffering (Dukkha), Gautama Buddha would have recorded this in his teachings. On the contrary, he, who promoted compassion and empathy for all sentient beings, professed precisely the opposite message.

Hate never ceases hate, in this world.

It is getting rid of hate [that manages to extinguish the flame of hate]: this law is universal. Na hi verena verāni sammantīdha kudācanaaverena ca sammanti esa dhammo sanantano (Dhammapada 5)

As we can only guess from the contextual analysis of these famous verses, social inequality, the shed blood of innocents, as well as the suffering of other beings (whatever their nature), were not issues that did not concern Gautama Buddha. Although nationalist thinking had not yet developed in the same way in his time as it will happen in contemporary history, the devastation resulting from the war between different kingdoms shares ethnocentric ideas with the Burmese conflict that the documentary addresses. Beyond the Buddhist apologetic discourse, from the academic point of view (I dare to say, precisely because of what concerns me), the teachings of Gautama Buddha historically promoted the practice of the four “shelters in Brahma”, which are nothing more than different ways of expressing the most human quality: empathy. Universal love, compassion, joy in the achievements of others, are the altruistic practices that he defined as restorative, first of all, for those who put them into practice, especially when they are carried out under the prism of equanimity (Upekkha). The activism of the punk-Buddhist band refers to the reflection (even if sometimes they express it with too much distortion on the guitar, for my personal taste) of these teachings. The Eightfold Path (Ariya Atyhańgika Magga) is the basis of the Buddhist ethical message. The Middle Way, the method that Gautama Buddha coined so that everyone could obtain their own liberation, involved more than mere words, doing what was right. What is right can be interpreted depending on the situation. Which isn't to say that doesn't mean doing the right thing. Gautama Buddha never denied the (individual) consciousness of the human being to discern what is right, quite the contrary. Despite the fact that Gautama Buddha and his group of followers completely renounced their social status, there is no doubt that throughout his life he encouraged philanthropy and altruism in all its possible forms. For him, doing the right thing is always what we ”Relay” with the most absolute truth. Kyaw Kyaw, does not question the individual's ability to achieve happiness either. Like Gautama Buddha, he seeks to promote people's awareness of this capacity, through his social activism. Which is nothing else, in my opinion, than his interpretation of compassion, the exercise that Gautama Buddha emphasized, serves to detach us from everything that binds us to continue suffering. Among the volunteer activities carried out by the Burmese punk group, the Food Not Bombs (“Food, not Bombs”, an international movement that began in the United States in the 1980s), where they distribute food to the people most in need. He and his punk band do not stop traveling to the most rural areas of the country with the aim of helping those most in need.

Not clinging, not even to Buddhism itself?

The renowned Chinese monk Línjì, founder of the school of Zen Buddhism that bears his name Yìxuán( read Rinzai in Japanese) left for posterity his message summarized in the phrase: ”If you meet a Buddha, kill him.” This shocking advice, although it might sound paradoxical to us, precisely advocated detaching ourselves from all kinds of Essentialism (a philosophical position that Buddhism denied from the beginning). Burmese religious fundamentalism, championed by certain sectors that consider themselves Buddhists, does not seem to be a particular trait of its people, despite what the Burmese national-centrist movement claims. The filmography that we review here, or rather, the central problem from which his story emerges, comes precisely from there, from the ethnocentric vision of those who fear the disappearance of their traditions. Interpret phenomena in a static way, as if they were ”independent things” (rather than interrelated processes) are far from what Gautama Buddha taught. For him, to hold on to an idea (Micchābhinivesa) stemmed from misinterpretation (Michadithi), which in turn has an impact on action (Micchākammanta) in a biased way (Micchāgahaṇa). Those who do this way (Micchācārī) direct your mind (Micchapanihita) in the wrong direction, which leads to continued suffering. The eagerness (Micchāvāyāma) and thoughts (Micchāsańkappa) that could be shown in everything that is done in this direction, which, we emphasize, clings to suffering, is the trigger of a false life (Michajiva). Some of the oldest passages in the Buddhist canon attached to the Theravāda school include the following as direct teachings of Gautama Buddha:

Knowing that this is suffering, when these experiences, when it is contemplated that these phenomena are false (Meosa), then the moment you contact them, your contact fades and you understand their nature (Dhamma). A self-respecting monk, [is the one] without hunger, eradicates his feelings and frees himself (Parinibbuto)

Age “Dukkhan” Ti Ñatvāna Mosadhamma PalokinaPhussa Phussa Vaya PassaEva Tattha Virajjati, Vedanana Khayā Bhikkhu Nicchāto Parinibbuto ti (Suttanipāta 739)

Knowing the danger of this, that “the flame of attachment” causes suffering, a monk must act consciously, acting free of attachment, without clinging [to anything]

Etam ādīnavañatvā taṇhā dukkhassa sambhavavītataṇho anādāno satvā taṇhā dukkhassa sambhava vītataṇho anādāno satbhikkhu paribbaje ti. (Suttanipāta 741)

In these passages, some of the oldest known in the Buddhist canon, the idea seems clear. El attachment And the hunger, are two metaphors that go beyond material belongings, let's not forget that, in the Buddhist monastic context, these have no meaning. So what does this refer to here? Basically to discard any kind of idea, or what is otherwise to get rid of ethnocentrism. The denial of an individual entity (Anatta), exercising compassion and altruism towards all beings, as well as many other Buddhist teachings, are nothing more than a call to that very thing. If we want to be even more concise and elaborate the argument, we will say that, in this way, the cognitive process (based on the desire of our consciousness to feed itself with stimuli) can be deconstructed. Let's see, what we consider to be real when we hold on to what we experience, is nothing more than the product of the interdependence between matter and consciousness, what keeps us within existence (Samsara). The deconstruction of the empirical process is the goal of Buddhist practice. If you meditate but hurt others, you are not a Buddhist. If you do punk, but you help others (you're also helping yourself, hence the idea that altruism is liberating), you are indeed a Buddhist. Being a Buddhist doesn't mean wearing a specific habit, but rather behaving in the right way. The right thing doesn't involve specific behavior, it depends on the situation. What is not relative is the direction that must take to be identified as correct. The objective is always the same, to counteract the effects of what causes suffering.

From the perspective of the leader of the punk group, certain sectors of his country's main religious tradition had tolerated, based on fundamentalism, first, that the political systematization of religion would result in it disconnecting from its original altruistic message, but above all that this would result in something that further contradicts its conciliatory message: hate and its greatest exponent, violence. The fundamentalism generated by religious orthodoxy is not unique to Burma. The strong link with the political sector of the Buddhist community in other Southeast Asian countries has allowed nationalist ideas to be supported under the pretext of not allowing what these people believe to be distorted. The conversation that the leader of the Burmese punk group, Kyaw Kyaw, has in the garage with other followers of his movement, testifies to the root of the discord. Kyaw Kyaw indicates that to understand and implement the Buddhist message in an integral way, what is truly needed is to “change oneself, from the heart”. The young man is appealing for something more than what has been established in his country as Buddhism. Their quest for spiritual freedom is more than remarkable. His channeler is punk, for him, his “Buddha”.

Final Thoughts

I am convinced that Gautama Buddha would not have liked punk music very much. In fact, I'm not even sure that, if I had listened to it, I would have considered it “music”, as such. Well, this is perhaps an overly subjective opinion of the author. Even so, what I have no doubt about is that Gautama Buddha would not have completely disapproved of the intention implied in the message of: “Punk is my Buddha”. For all lovers of humanism, the modern history of Burma, but above all to observe how certain people have overcome adversity and fight to defend the Truth, deserves a visit to the newspaper library, in addition to a deep personal reflection.

Recommended articles related to the documentary

https://www.nytimes.com/es/2019/07/11/espanol/birmania-budismo-musulmanes.html

https://www.punkethics.com/rebel-riot-interview/

https://www.sandrahoyn.de/portfolio/the-punk-of-burma/

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/09/saffron-revolution-good-monk-myth/541116/

Dhammika Herath. (2020) Constructing Buddhists in Sri Lanka and Myanmar: Imaginary of a Historically Victimised Community. Asian Studies Review 44:2, pages 315-334.

McCarthy, Stephen (2008). “Losing My Religion? Protest and Political Legitimacy in Burma”, Griffith Asia Institute Regional Outlook Paper, No. 18.

Steinberg, D. (2008). Globalization, Dissent, and Orthodoxy: Burma/Myanmar and the Saffron Revolution. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 9(2), 51—58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43133778