This article is part of our special edition “Buddhism and Cinema”

There are artists who strive to aestheticize their own lives, to endow them with a distinctive color, a mythological aura in the search for magic in their lives, Literary. In many cases you can see the seams, you can smell the postin, the boredom that underlies the aureole. There are others — very, very few — who do it unaffected, whose lives seem to be dominated by a secret motive, possessed by a demon that will lead them to unexpected and tragic places. Yukio Mishima is one of these: his literary work cannot be separated, in retrospect, from the biographical fact that he founded a kind of ultra-nationalist militia with which he would end up kidnapping a general and haranged the armies to carry out a coup d'etat in Japan, a failed assault that culminated in the ritual suicide of the writer and one of his followers. Such madness was not the work of a third-rate author seeking posthumous fame, but of a strong candidate for the Nobel Prize. This dramatic ending of the samurai, whose alternation of heroism and derision seems designed for 20th century lenses, will mark the writer's entire posterity. Considered one of the main stylists and renovators of Japanese prose, Mishima will also be, after his death, a symbol for ultra-nationalist, subversive and radicalized movements. A threat to the peace and order of the nation, whom the prime minister of the time described as a man “out of his mind”.

Although film adaptations of his work proliferated during Mishima's lifetime, after his suicide (1970) he began to be prevented by Japanese celluloid. In the following three decades, we found only a handful of remote titles (such as Kinkakuji [1976] or several re-enactments of The sound of the waves). Some foreign directors showed interest, for example, Paul Schrader in Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), which intertwines the life and work of the “coup” writer and took forty years to be screened in a Japan that until the 21st century maintained a film veto against the writer. In the 1950s and 1960s, Mishima had acted in films such as the Yakuza Afraid to Die (1960) and even addressed himself based on one of his stories (Patriotism or the Rite of Love and Death, 1966), staging of a Seppuku which the widow ordered destroyed (fortunately, some negatives escaped her). The best-known film about his work is still the one made at the time by Kon Ichikawa, who would adapt, together with his wife and co-screenwriter Natto Wada, the novel The Golden Pavilion On a tape called Enjō: 'Conflagration' (1958).

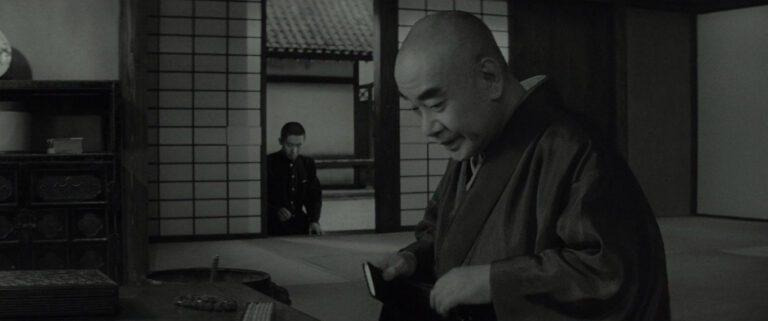

Gōichi Mizoguchi is the son of a Buddhist priest who enters the temple of the pavilion that gives title to the novel to train in the profession. Although we will have to wait for The Temple of Dawn for a deeper immersion in Buddhism, which took the writer to India and the Ajantā caves, The Golden Pavilion offers a peephole at what Mishima (and any neighbor's son) could see in the Establishment clerical “zen”. A disenchanted lens that Ichikawa's camera delicately reconstructs, focusing on the hypocrisy of hierarchical interactions and the network of mutual occultations, from evening outings to a bottle of cologne in a box. Time goes by in a routine where the recitation of Sūtras or financial management that meditation and discussion of Kōans or Zen riddles, although we will witness a lesson about the famous episode where Master Nansen kills a cat that was the subject of discussion (collected in The Immortal The Door Without a Door). “If you can say a word, I'll forgive the cat. If not, I'll kill him.” It kills him.

A slow monastic life, without major shocks or scandals, except for a few visits to GeishaThey are socially accepted in a monasate that had abolished celibacy the previous century (Mizoguchi is not the only “son of a monk” who is sent to the temple to learn the profession of his caste). The protagonist, on the other hand, resents these minor corruptions, as well as the inquinine crosses around him and the antagonism towards his person due to his stuttering and perceived favouritism. To this are added family trauma and an obsession with the ungraspable beauty of the historic golden pavilion, a combination of frustrations and complexes that will lead him down the slope of the final conflagration.

Faced with such a “cinematic” novel, abundant in associations and visual juxtapositions, with recurring meditations on beauty, a modern-day filmmaker would easily fall into the temptation to chain together dreamlike or visionary transitions. Ichikawa, on the other hand, shows off a clear line, a sober realism that doses lyricism. We are (still) in the 1950s, and the narrative material is pruned for consumption by the spectator of the time: the female breast —one of the visual motifs in the book— is not even insinuated and the always troubled protagonist appears a little more like a victim of society, since we are not given access to his thoughts. In this sense, the film is the negative of the novel: there it is monologuistic, here impenetrable. The lack of an inner narrative requires a more predictable character, who purges twists that would be inexplicable, as a first test of amorality: in the original, the prostitute does not have an abortion as a result of a struggle, but because Mizoguchi steps on her belly at the suggestion of the American client. The contours are softened, the psychology is simplified, but what is narrated can continue to impact.

Apparently, Kon Ichikawa considered this his favorite film of those he shot. We didn't buy the bet from him (in a catalog that ranges from The Burmese harp To the spectacular An Actor's Revenge, passing through the grandmother of Twin Peaks, The Inugami Family), but we understand that recording it would feel like a leap in the void. It is a film that foreshadows the “new wave” of Japanese cinema, like a Teshigahara released to its air in a city of temples. The custom of monastic life is accompanied by unsettling strings and dramatic angles, hints of the strange reminders of this filmic trend that for many will be born two years later with Cruel Story of Youth, by Nagisa Ōshima, another story of adolescent crime and rebellion (which apparently are the ideal subjects to usher in “new waves” of cinema, both in Paris and in Kyoto). Its rarefied atmosphere, its bold editing and its warning about the fatal weight of the eyes of others make Enjō a surprisingly “modern” production.

Anyone who wants to learn about the life of a Buddhist monk will only learn here the fundamentals (good and bad) of the life of a monk from anywhere. As we said, Mishima had not yet shown literary interest in Buddhist thought, which he never incorporated into his martial and obsessive way of living life anyway. On the other hand, for an Ichikawa just arrived from The Burmese harp, who had turned the condition of the mendicant monk into a debated pacifist icon (Bhikkhu), it may be this connection that drew him to the story, although the lesson he takes from Buddhism is that conflicts are resolved by killing the cat.