This item is part of our special edition: “Deciphering Chinese Buddhism”

You can read the previous article in this series by clicking here

III. Strategic importance, commercial dynamism and Silk Road centers

In this second installment—which continues sections I—II of Part I—we trace the route of the caravans that made the Silk Road the main artery through which Buddhism reached China. We stop at key centers—oasis-cities, road junctions, temples and monasteries—essential to understanding the cultural synthesis that Buddhism experienced before arriving in the Empire of the Center. In these nerve points, the teachers and translators who entered China were formed, not only as mere linguistic mediators, but also carrying doctrinal interpretations and nuances developed in these regions, which profoundly influenced the initial understanding of Buddhism on Chinese soil.

The Dharma did not travel along the Silk Road as ideas “in the air”, but on the backs of camels and horses. It was brought with them by Sogdian, Kushana and other merchants, dedicated to the lucrative exchange of silk, jade and spices, either along the routes north and south of Taklamakan or along the Hexi corridor to Luoyang. In addition to muleteers, guides, camels, diplomats and escorts also marched along the Route. His entourages were joined by monks —Gandharans, Parthians, tocharians—who acted as preachers, translators, compilers, copyists of sutras, meditation teachers and experts in the liturgy. All this is supported by a large infrastructure of oasis cities, customs, warehouses, garrisons and monasteries, such as those of Kucha, Turfan, Khotan and Dunhuang.

The symbiosis between merchants and monks

The collaboration between merchants and monks was decisive: merchants financed trips, sutra translations and the construction of monasteries and artistic works, such as the Dunhuang caves, in exchange for social prestige and spiritual merit. The monks, for their part, offered preaching, ritual services and ethical advice, while benefiting from the protection and hospitality of the caravans.

These commercial, administrative and military logistics made a profound religious change possible. At these geographical and cultural crossroads, where monasteries, warehouses and customs shared neighborhoods, economy and religion advanced hand in hand, forging a dynamic network of exchange and adaptation in which Buddhism not only reached new territories, but also evolved: it changed languages —from Sanskrit to Chinese, from Tocharian and Sogdian—, it adjusted rituals to integrate with local traditions and diversified schools —with the rise of Mahāyāna in Central Asia—, until it took strong root in China.

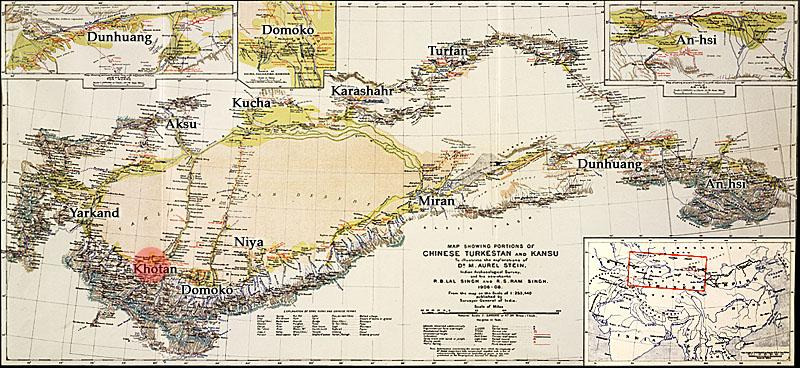

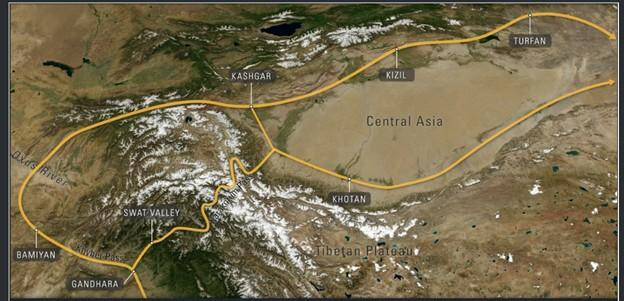

The two branches of the Silk Road: surrounding Taklamakan

Between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE, the Silk Road was configured as a vast network of roads that, crossing the Tarim basin, bifurcated into two large branches —one north and the other southern—to border the inhospitable Taklamakan desert. Both converged at Dunhuang, a strategic oasis known for its caves and manuscript deposits. From there, the Hexi corridor —protected by customs and fortified garrisons— was accessed, which guaranteed safe transit to inner China and the capitals of the Han empire: Chang'an in Western Han and Luoyang in Eastern Han.

The Northern Route: It started in Kashgar and passed through Kucha, Karashahr and Turfan; it continued to Hami and Dunhuang. This route, preferred in times of political stability, offered better resources and conditions.

The southern route: Also starting from Kashgar, it crossed Yarkand and Khotan, continuing at the foot of the Kunlun Mountains through Niya, Qiemo and Loulan until it met at Dunhuang. Although drier, this alternative was vital when the northern route was compromised.

The choice of one or the other path depended on factors such as season, safety, river flow and the availability of grass, in addition to local pacts and current conditions. These enclaves were not simply points of provision and rest, but prosperous kingdoms and city-states that acted as cultural locks.

Anatomy of a Journey: Dharma Laboratories on the Route

To understand how Buddhism came to China, it's not enough just to draw lines on the map; you need to stop at the stops. Oasis cities were laboratories of religious transformation where Dharma was “cooked” at low heat: it was translated, debated and adapted to new cultural realities. The trip progressed at a slow pace of between 25 and 40 kilometers per day, rigorously adjusting the stages to the location of the wells.

1. Forges of Transformation: Gandhāra, Bactria and Samarkand

Before entering the Tarim basin, Buddhism acquired intellectual and logistical tools in three major Western centers:

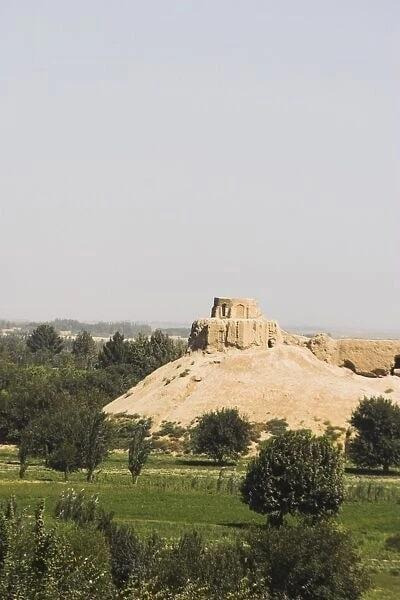

Gandhāra and the materiality of the text: In this Indo-Hellenic kingdom, the image of the Buddha was shaped with his Apollonian features and the folds of his robe. Here the transmission support changed: the texts ceased to be only oral and were fixed on birch bark rolls, light and easy to transport. These writings were mostly written in Gandhārī or Prákrit, using the Kharoṣthi script. Along with them, iconographic repertoires carved from sandstone or schist circulated, which served as visual guides for preachers.

Bactria and transit: Through the city of Balkh and the Nava Vihāra complex, the figure of the interpreting monk became professional. Bactrian monasteries acted as guardians of the itinerant sainga: they prepared letters of introduction, protected gifts (Dāna) and synchronized the religious calendar with the times of the caravans.

Samarkand and financial power: Sogdian merchants incorporated monks as “prestigious passengers”. This symbiosis was complete: merchants provided armed security in exchange for spiritual merit and ritual protection for their businesses. In Samarkand, terminological uses were consolidated between Sanskrit and several vernacular languages, facilitating the circulation of concepts and giving greater coherence to translations.

2. The Northern Route: The Intellectual Corridor and Translation

After crossing the difficult mountain passes of Fergana, the caravans arrived in Kashgar. Those who opted for the northern route entered a corridor of great intellectual activity:

Kucha (Kucha): The most influential center of the northern branch. It was a cultural powerhouse that rivaled Indian centers and became famous for its Abhidharma studies. It houses testimonies from great Scriptoria (translation workshops) from which figures such as Kumārajīva emerged. Their translation teams fixed much of the Buddhist terminology that would later prove influential—and in some cases normative—in China.

Turfan (Gaochang): Under the patronage of local elites — and, in later stages, Uighur authorities — texts were copied in Sanskrit, Sogdian, Uighur and Chinese. It functioned as the last major cultural customs office before China proper.

3. The Southern Route: Devotion, Jade and Silence

The southern route was markedly drier, but essential for devotional practice and art.

Khotan: Famous for its silk and jade mines, it became a bastion of Mahāyāna Buddhism. As the Faxian pilgrim would recount, the monastic density was astounding, with image processions that paralyzed urban life (Legge, 1886:16).

Niya and Loulan: In this stretch, monastic infrastructure became vital for survival: small sanctuaries and wells sewed the void of the desert, offering the only physical and spiritual refuge.

Dunhuang and the Hexi Corridor: the great cultural lock

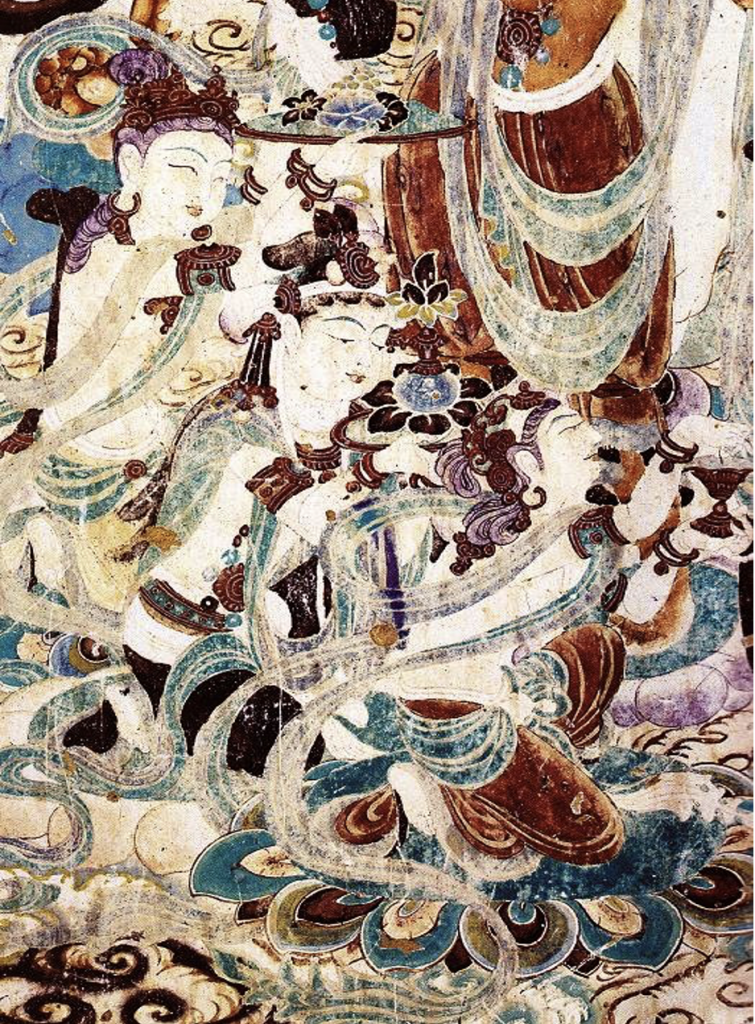

Both branches inevitably converged at Dunhuang, China's “gorge”. This oasis was the ultimate laboratory of adaptation. The Mogao Caves, carved into the nearby cliffs, are the stony testimony of this process.

The famous Cave 17 (Library Cave), sealed in the 11th century and rediscovered in 1900, revealed an archive of more than 40,000 pieces (Whitfield, 2004, p. 22). The fascinating thing is that his archives not only contained sublime sutras such as Diamond Sutra (868 CE.); together with the doctrine, they kept loan contracts, medical prescriptions, shopping lists and administrative documents in Chinese, Tibetan, Sanskrit, Sogdian and Uighur. This suggests that monasteries acted as one of the region's main social and economic centers, in addition to fulfilling religious functions. There, Buddhism began to cease to be perceived as entirely foreign: it was retranslated, recontextualized and prepared to circulate in understandable records for growing sectors of Chinese society.

In addition, Dunhuang was a major focus of visual culture. In the Mogao caves, murals and sculptures were not an ornament, but part of a ritual and devotional environment: they showed scenes from the life of the Buddha, exemplary stories (jataka) and “pure lands” that guided the religious imagination at a crossroads of routes and languages. Due to its scale, its continuity over centuries and the richness of its iconographic programs, Mogao became an extraordinary group in Buddhist art.

From Dunhuang, Buddhism finally entered the “mouth” of the empire through the Hexi Corridor. This strategic corridor was heavily militarized and protected by the Jiayuguan Fortress (the western end of the Great Wall). Garrison cities such as Zhangye, home of the reclining giant Buddha, and Wuwei provided the “last mile” of the journey. In this section, the teachings passed through the filter of imperial customs until they culminated in the capitals, Chang'an and Luoyang. There, under imperial patronage, large scale translation offices were established where teams of scholars systematized the legacy received from the oases (Sen, 2003, p. 60).

IV. Context of spiritual crisis and search for meaning in China

The arrival and entrenchment of Buddhism in China can hardly be understood as fortuitous; they must be placed in the context of the progressive collapse of the Han dynasty. It was a period marked by economic crises, palatial intrigue and generalized violence, which created especially favorable conditions for a foreign religion to settle.

The collapse of official ideology

This scenario was traumatically manifested in the Yellow Turban Rebellion (184 BC). More than a peasant revolt, it was a phenomenon with a religious component and millennial expectations; a symptom that social unrest had spread. This conflict highlighted the limits of state control and weakened the Confucian imaginary that linked virtue and cosmic order. In this context, the idea of the Mandate of Heaven was strained in the face of the reality of civil war and epidemics.

Buddhism did not arrive at a passive vacuum, but rather at a space of active search. In the first moments it was read through local categories, sometimes through the Geyi (or “pairing of concepts”), a process of adaptation that, not without equivocation, gradually revealed its own philosophical complexity.

A machine of meaning

The loss of predictability undermined trust in state orthodoxy and opened up a new social demand: effective protection from misfortunes, an intelligible sense of suffering, and ways to live in uncertainty. The appeal of Buddhism lay both in its diagnosis of pain (Dukhkha) as in the provision of mental cultivation techniques—attention and meditation—that offered recognizable subjective benefits. Thus, in addition to offering individual comfort, Buddhism was able to operate as a “machinery of meaning” and, in certain contexts, contribute to forms of social cohesion.

Conclusion: Dharma as a Bridge Between Civilizations

In retrospect, the arrival of Buddhism to China was a complex process of cultural metamorphosis. The Silk Road was not a mere passive conduit, but an immense gestation laboratory. From the centers of Gandhāra to Scriptoria from Kucha and the Dunhuang Caves, each oasis functioned as a resonance chamber where the Dharma stripped of its Indian clothing to dress in languages and concepts understandable to the East Asian mentality.

This transmission was made possible by a unique historical convergence: the imperial infrastructure of the Han and the symbiosis between monks and merchants created logistics; the spiritual crisis at the end of the dynasty generated demand. China didn't just receive Buddhism; it absorbed it, translated it and reinvented it. The caravans carried the seeds, but it was the interaction between the geography of the Route and the historical need of the Middle Kingdom that allowed those seeds to flourish, making Buddhism one of the three fundamental pillars of Chinese culture for the coming millennia.

Bibliographic References

Ch'en, K.K.S. (1964). Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey. Princeton University Press.

Hansen, V. (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press.

Law, J. (1886). A Record of Buddhist Kingdoms... Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lewis, M.E. (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Harvard University Press.

Salomon, R. (1999). Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhāra. University of Washington Press.

Sen, T. (2003). Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade... Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

Vaissière, É. (2005). Sogdian Traders: A History. Brill.

Whitfield, S. (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library.

Zürcher, E. (1972). The Buddhist Conquest of China. Brill.

You can read the next article in this series by clicking here